Generation

2017 - 2019

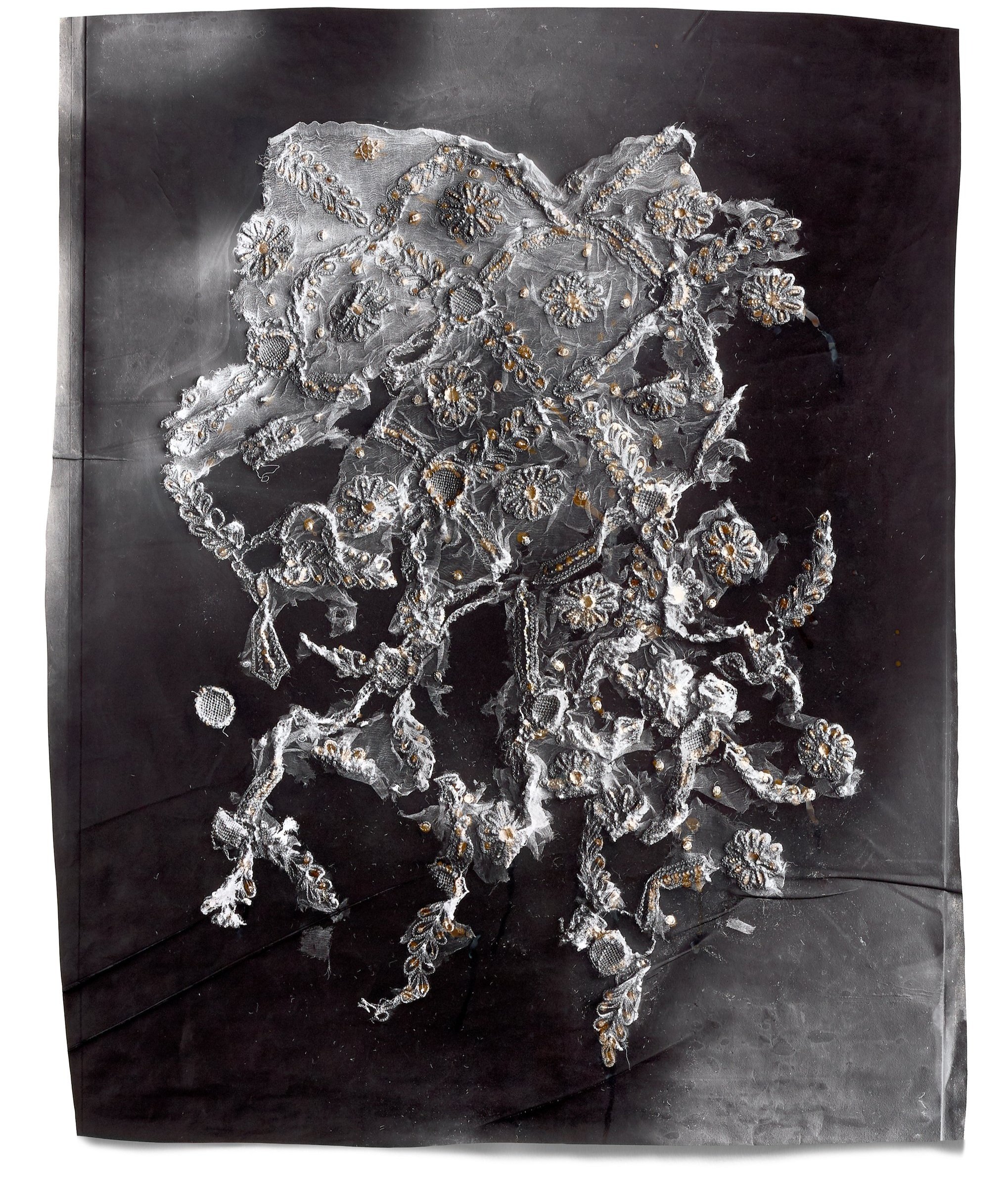

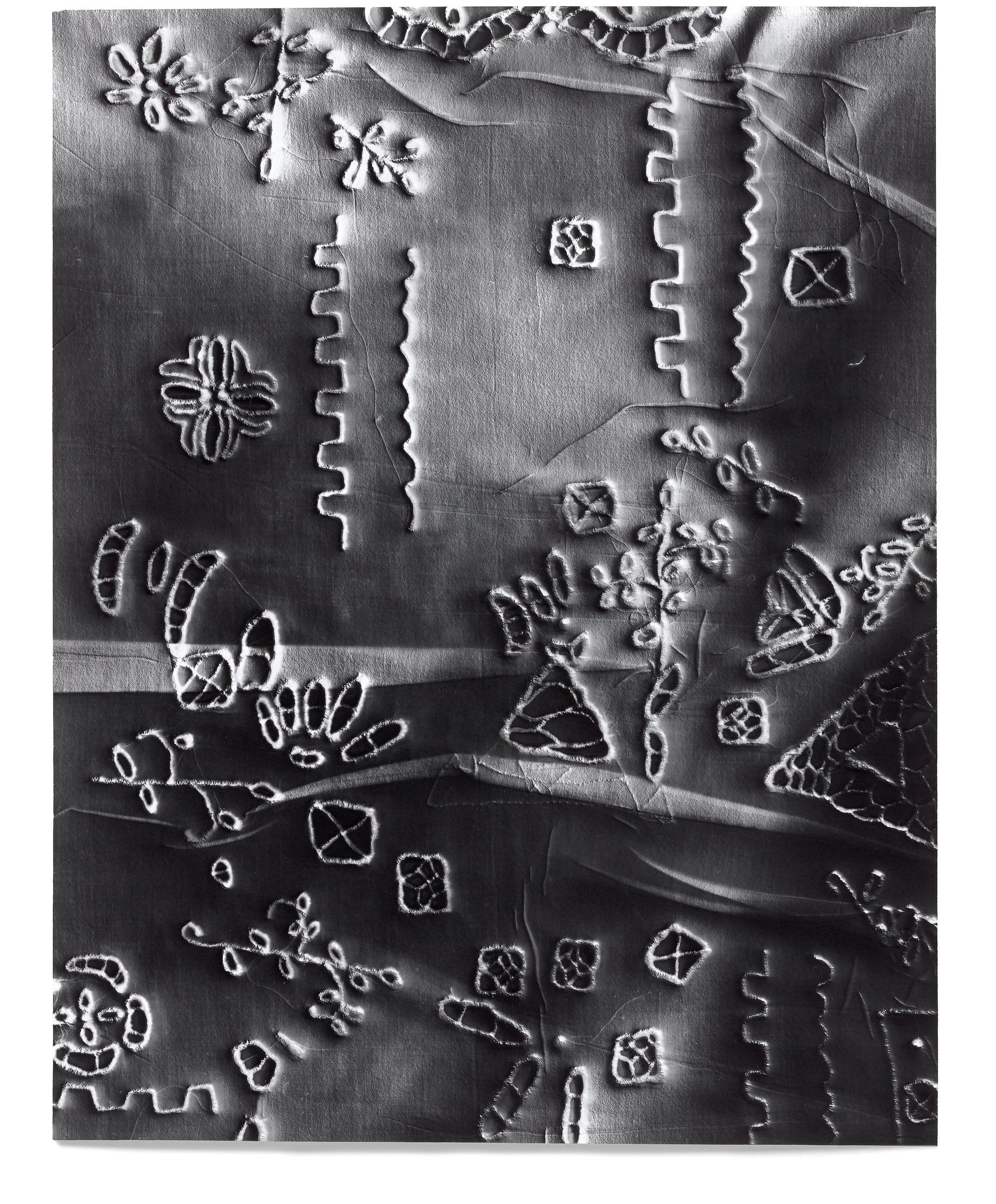

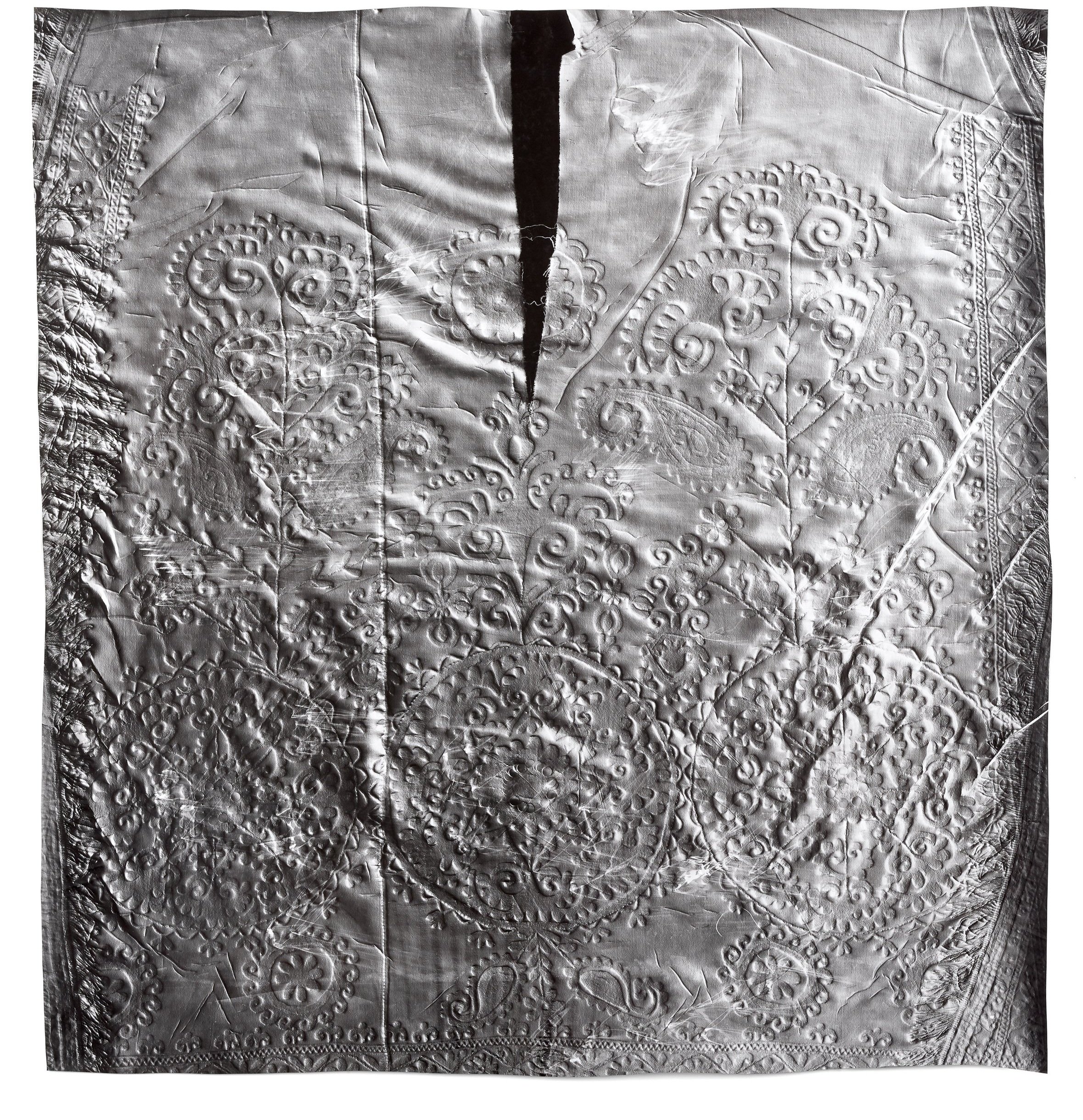

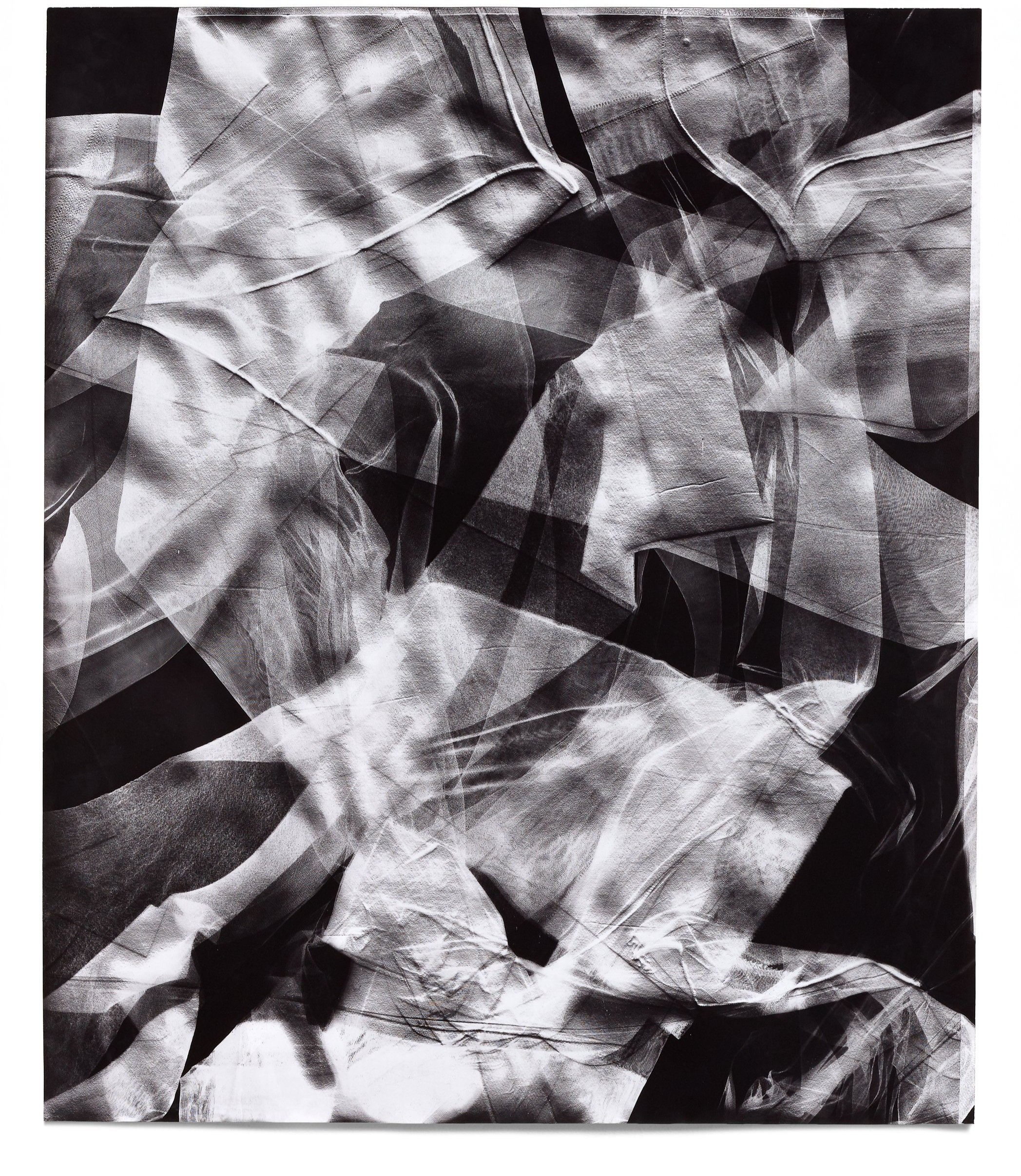

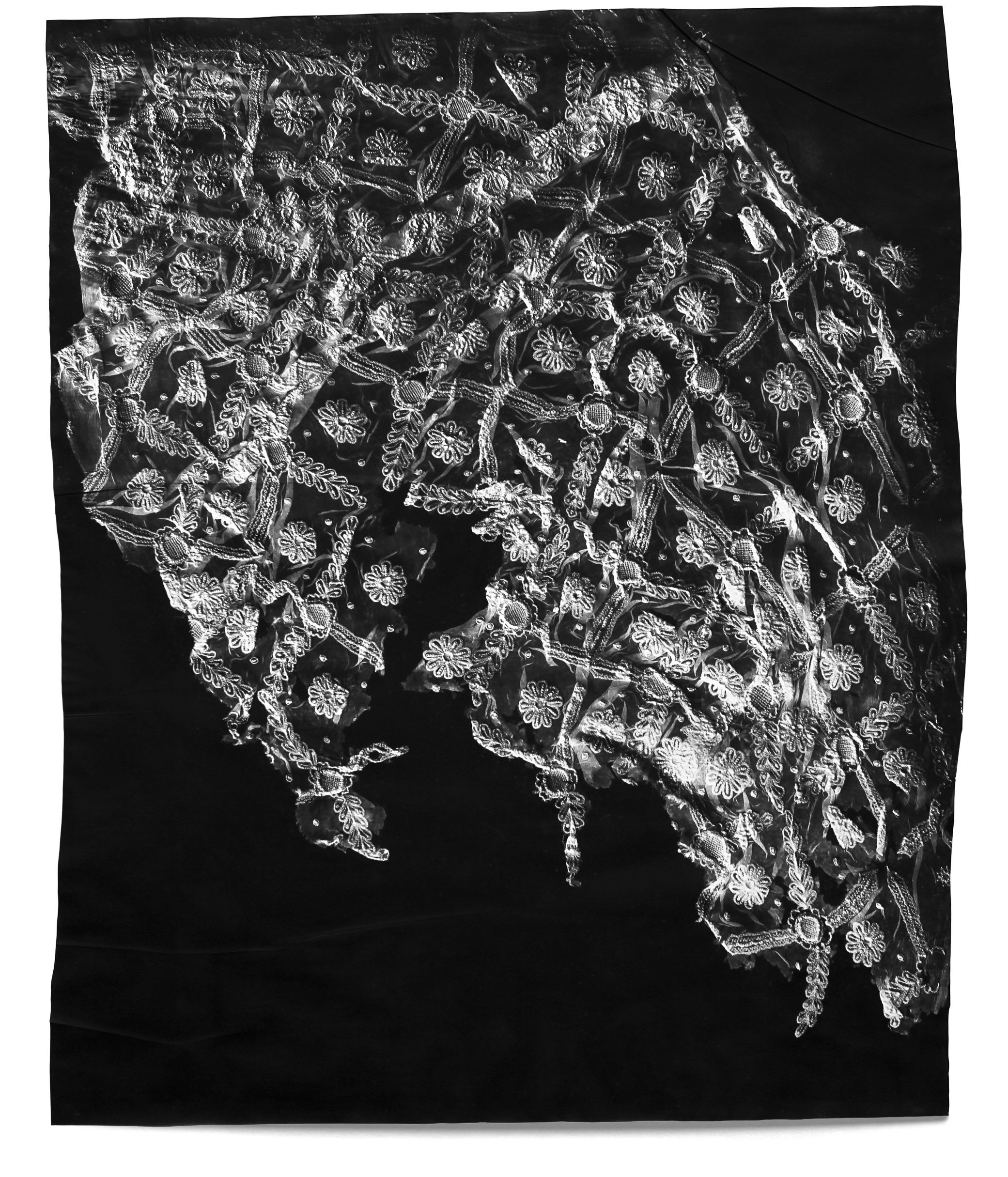

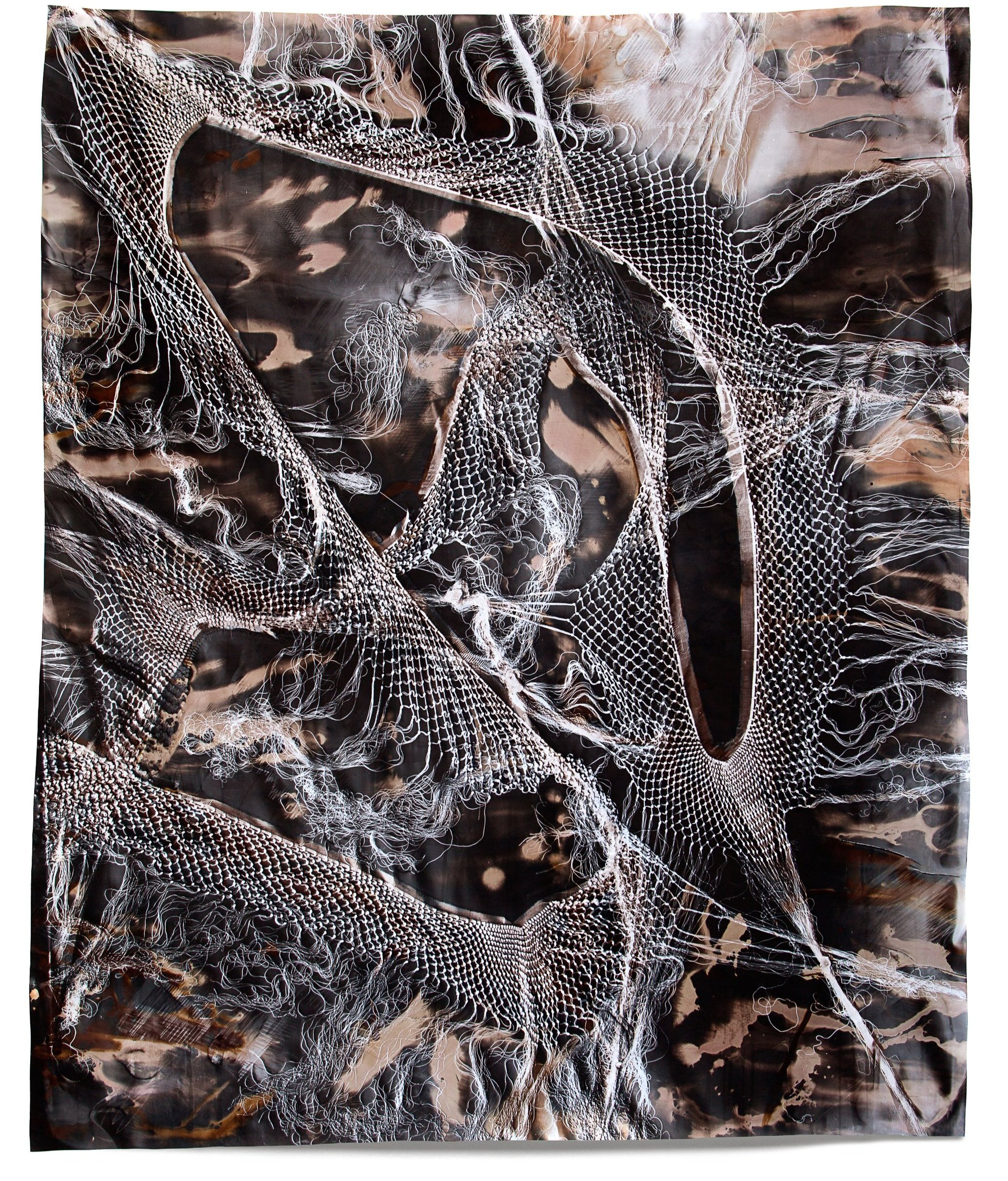

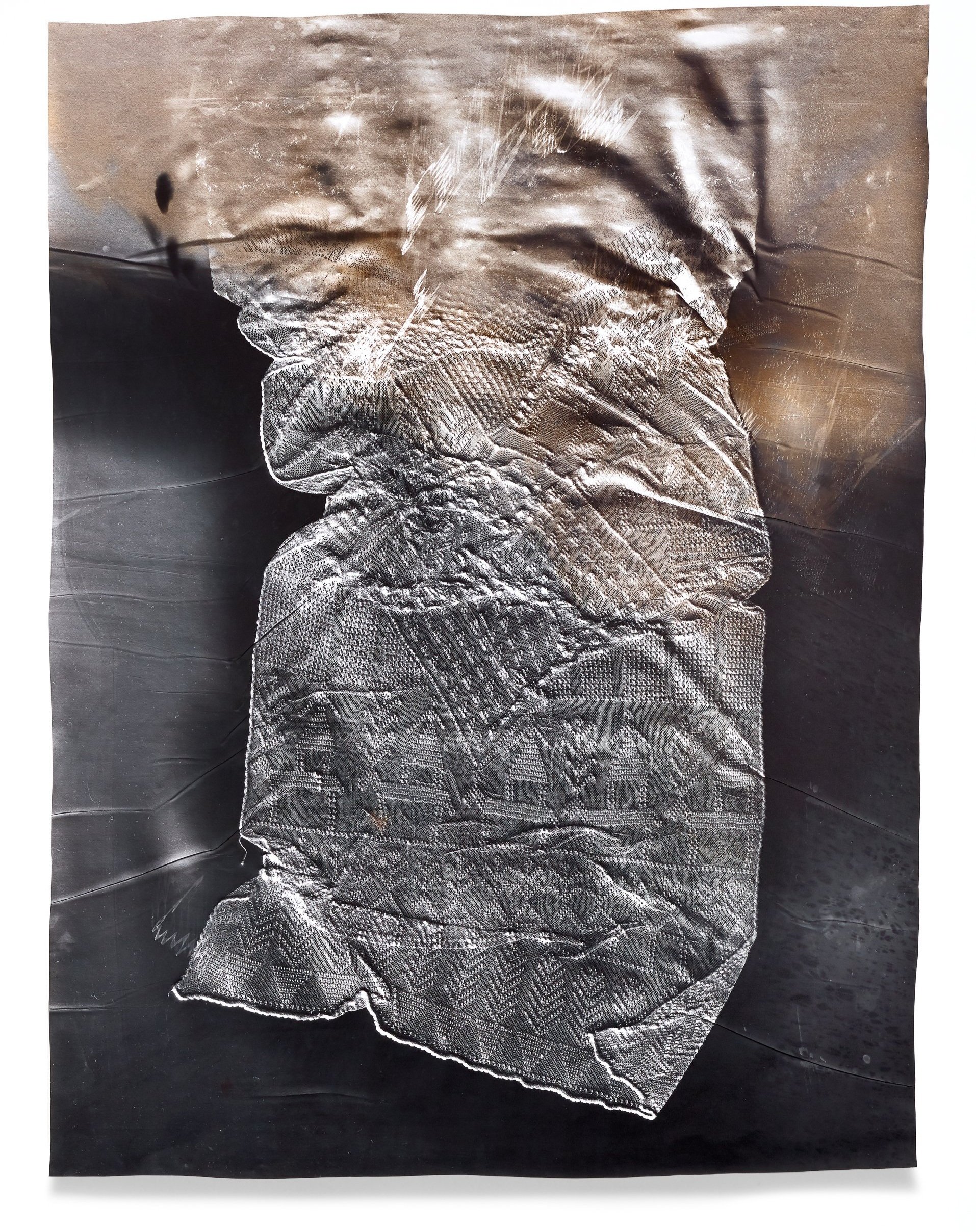

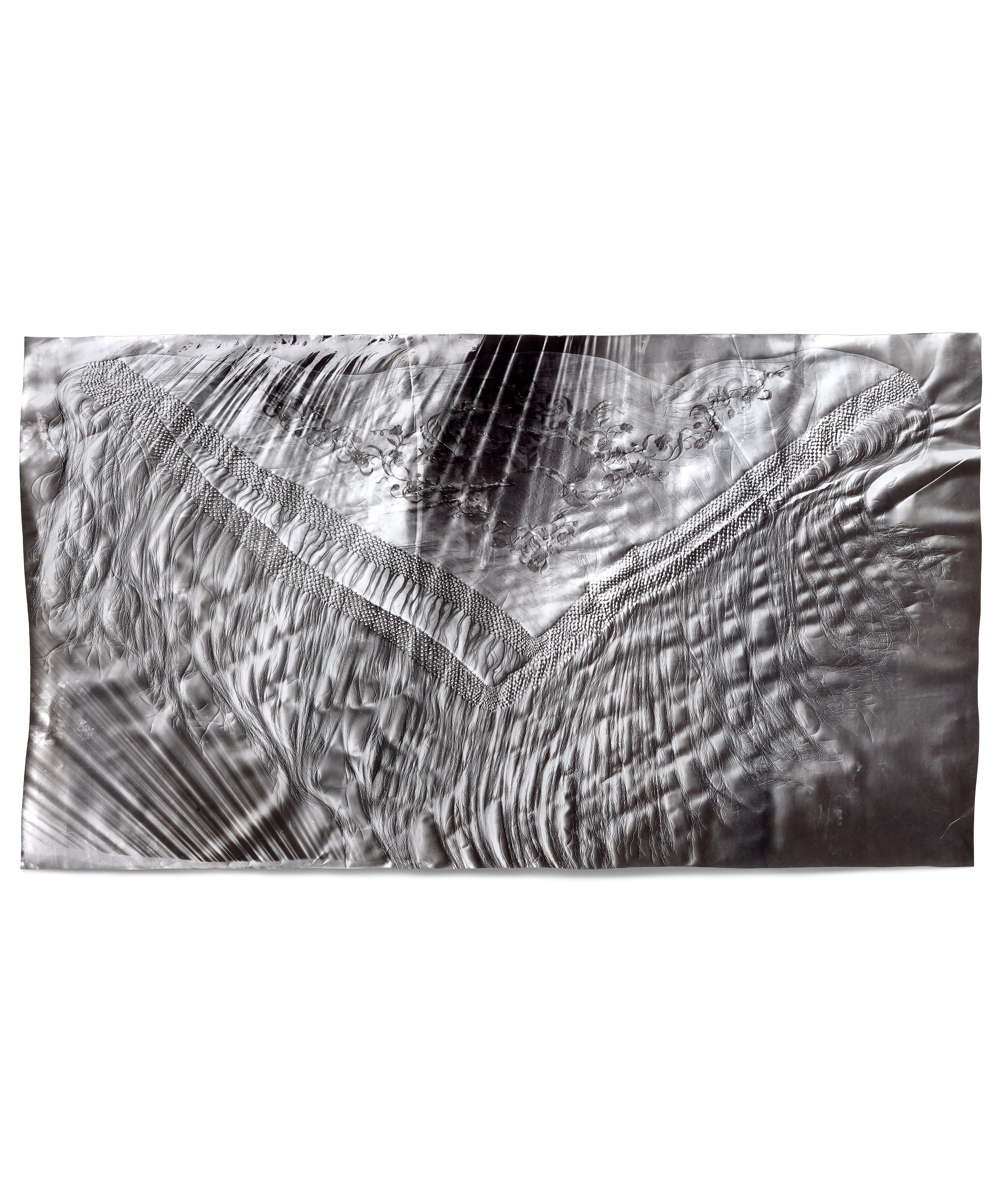

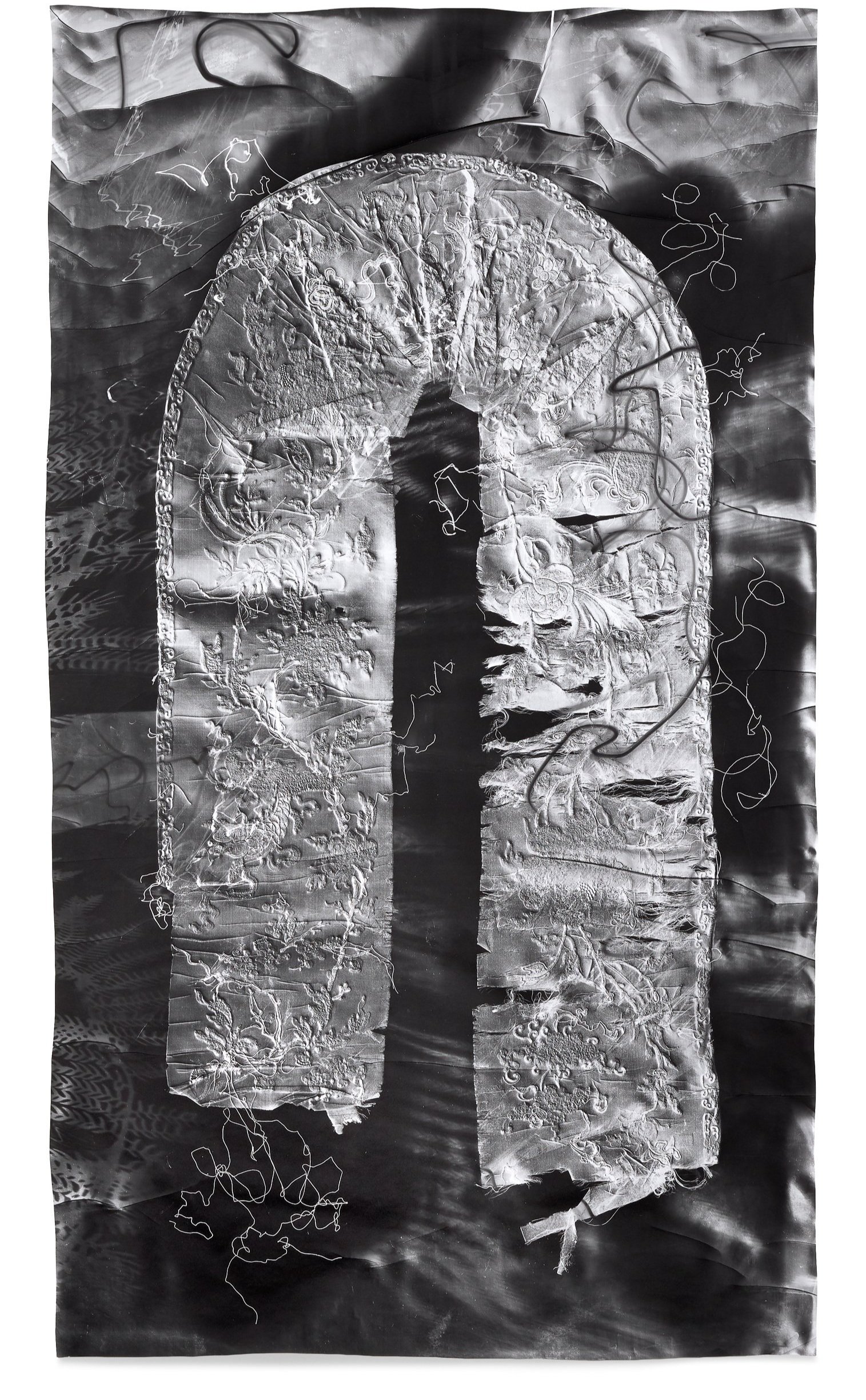

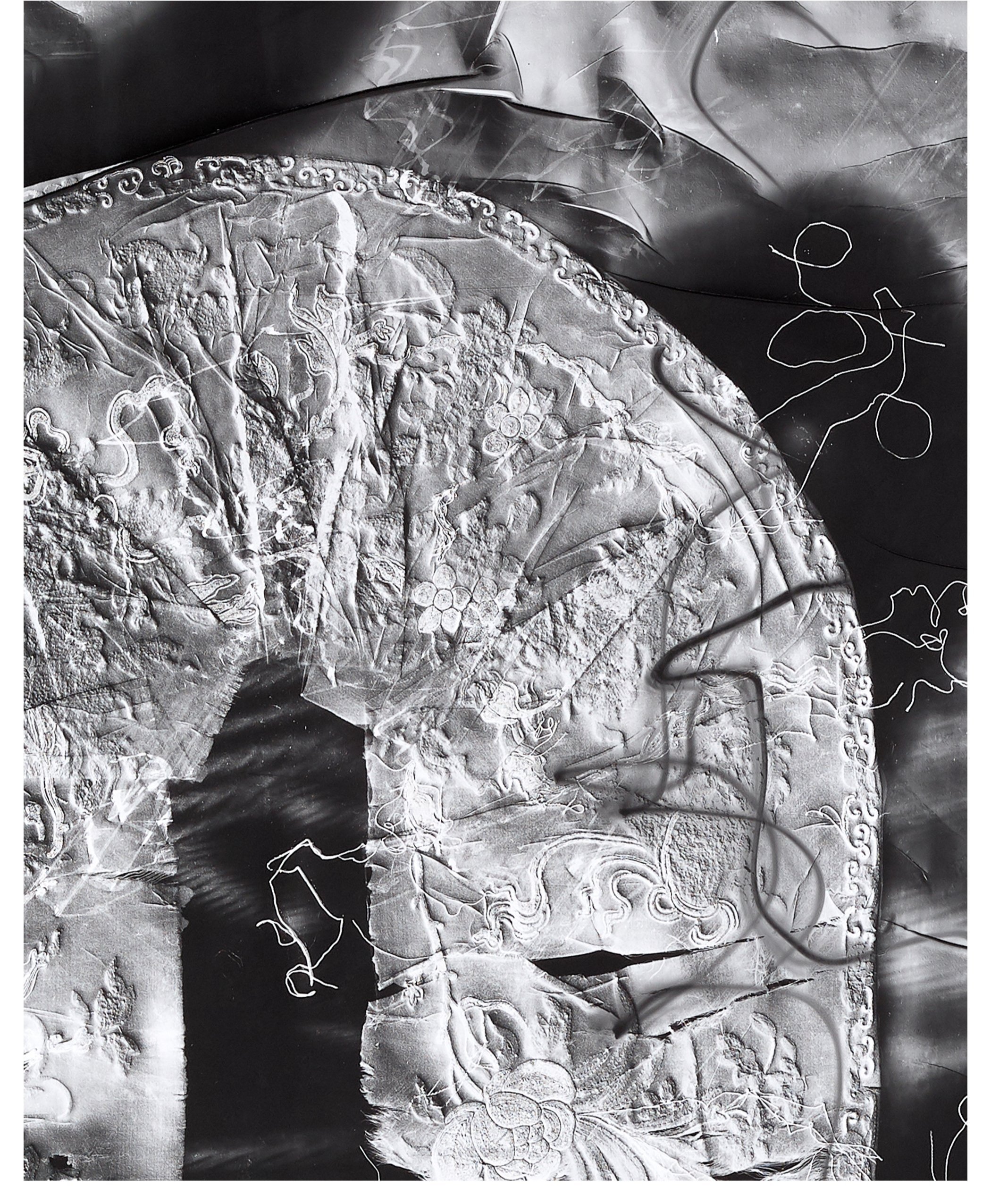

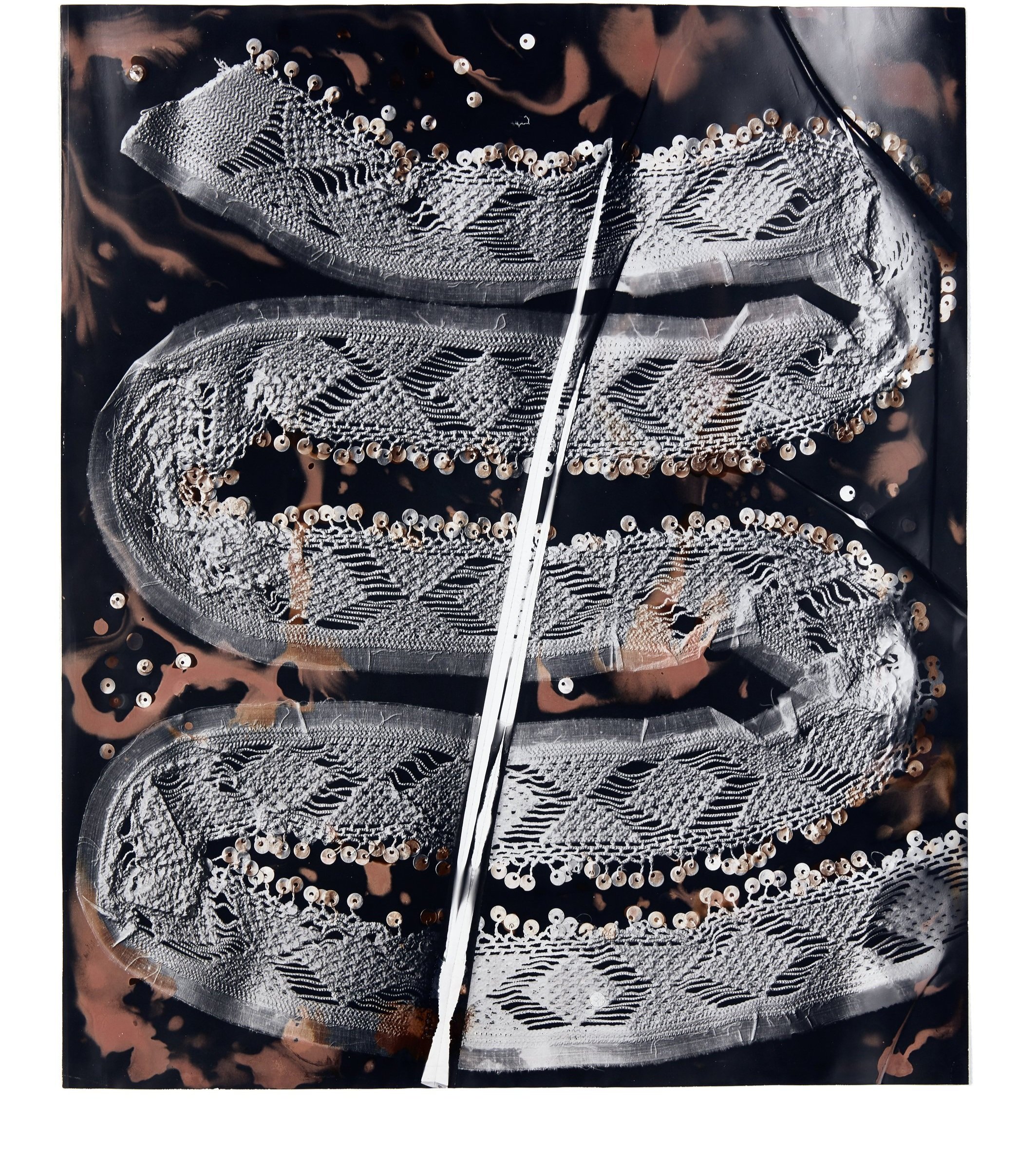

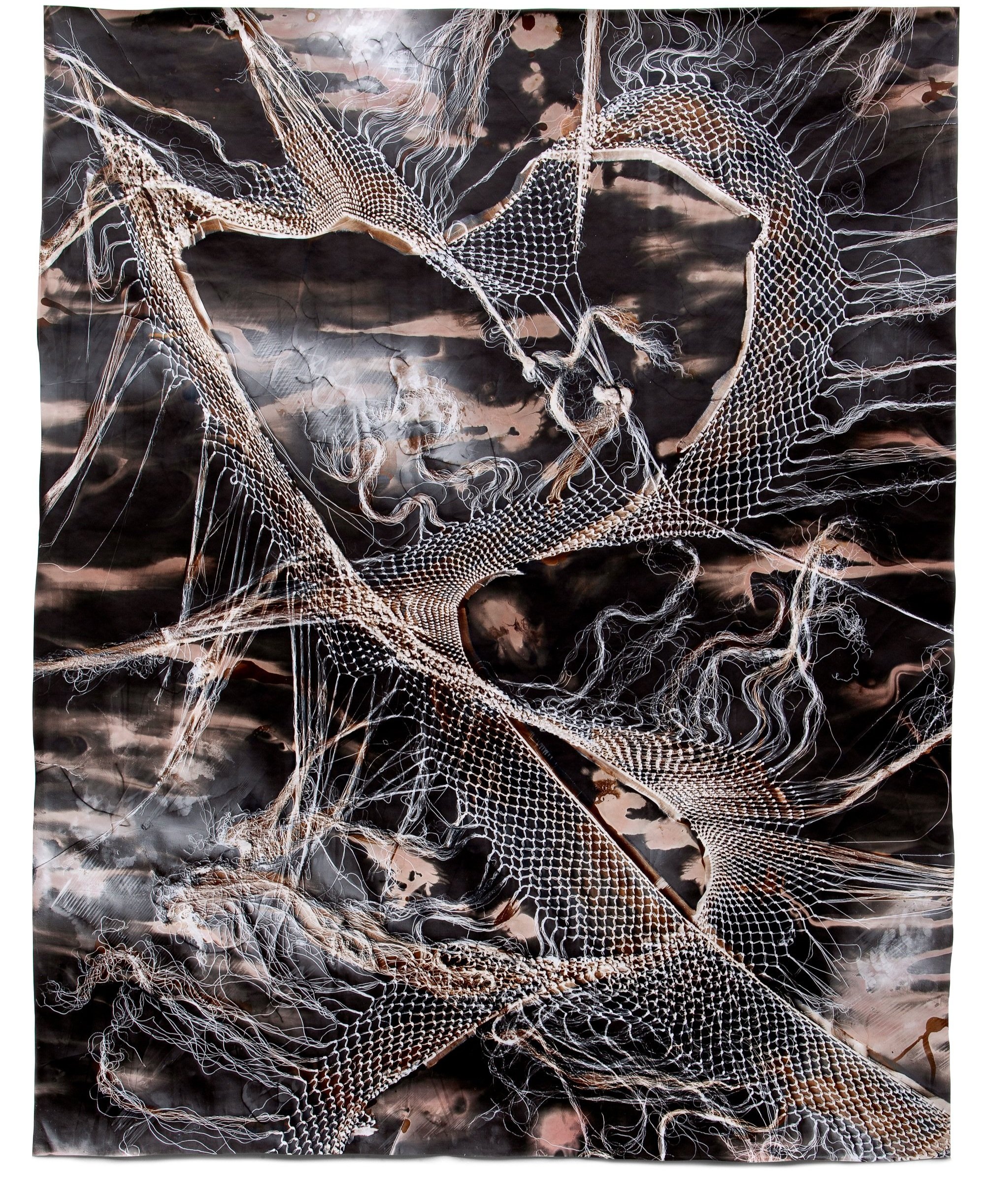

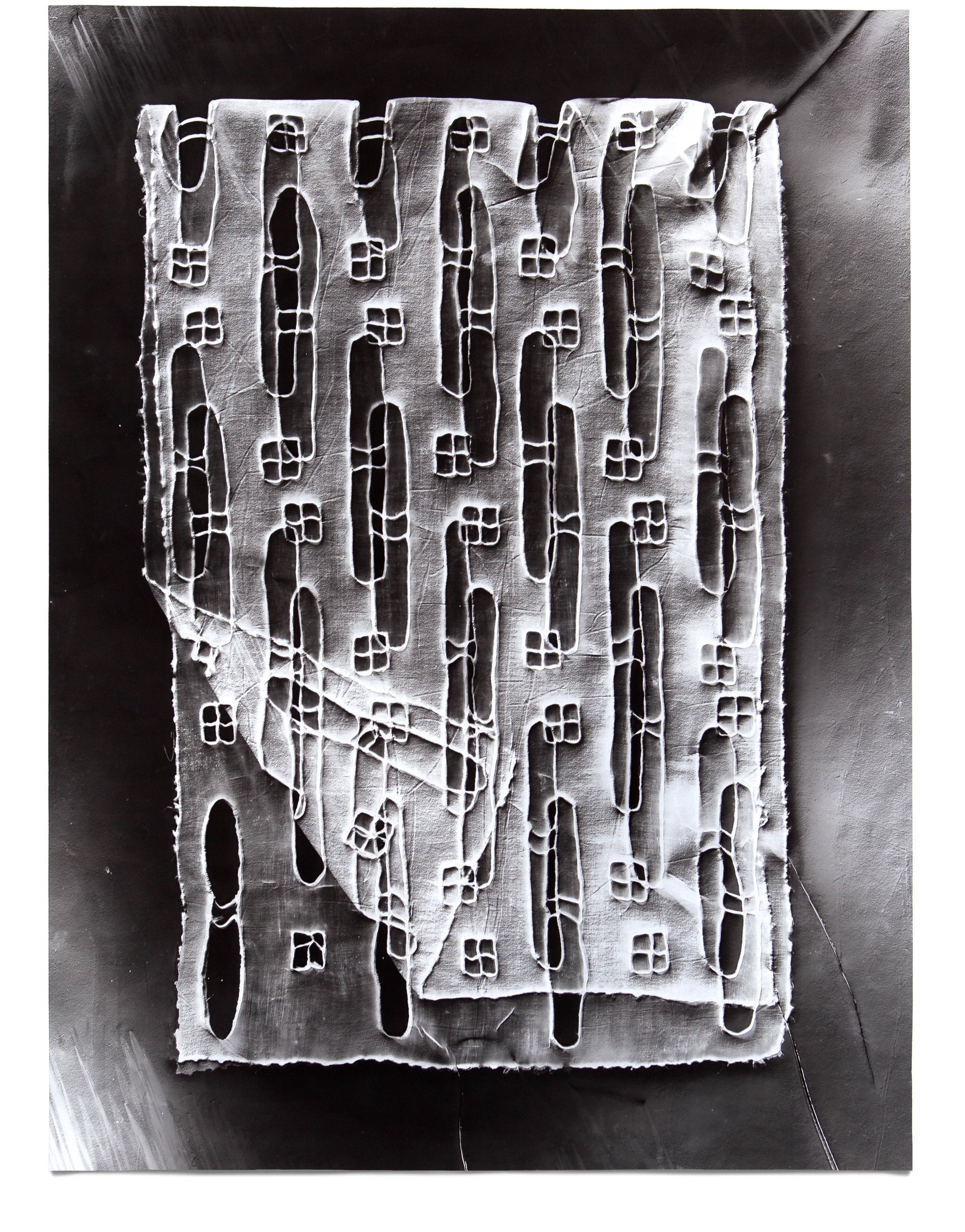

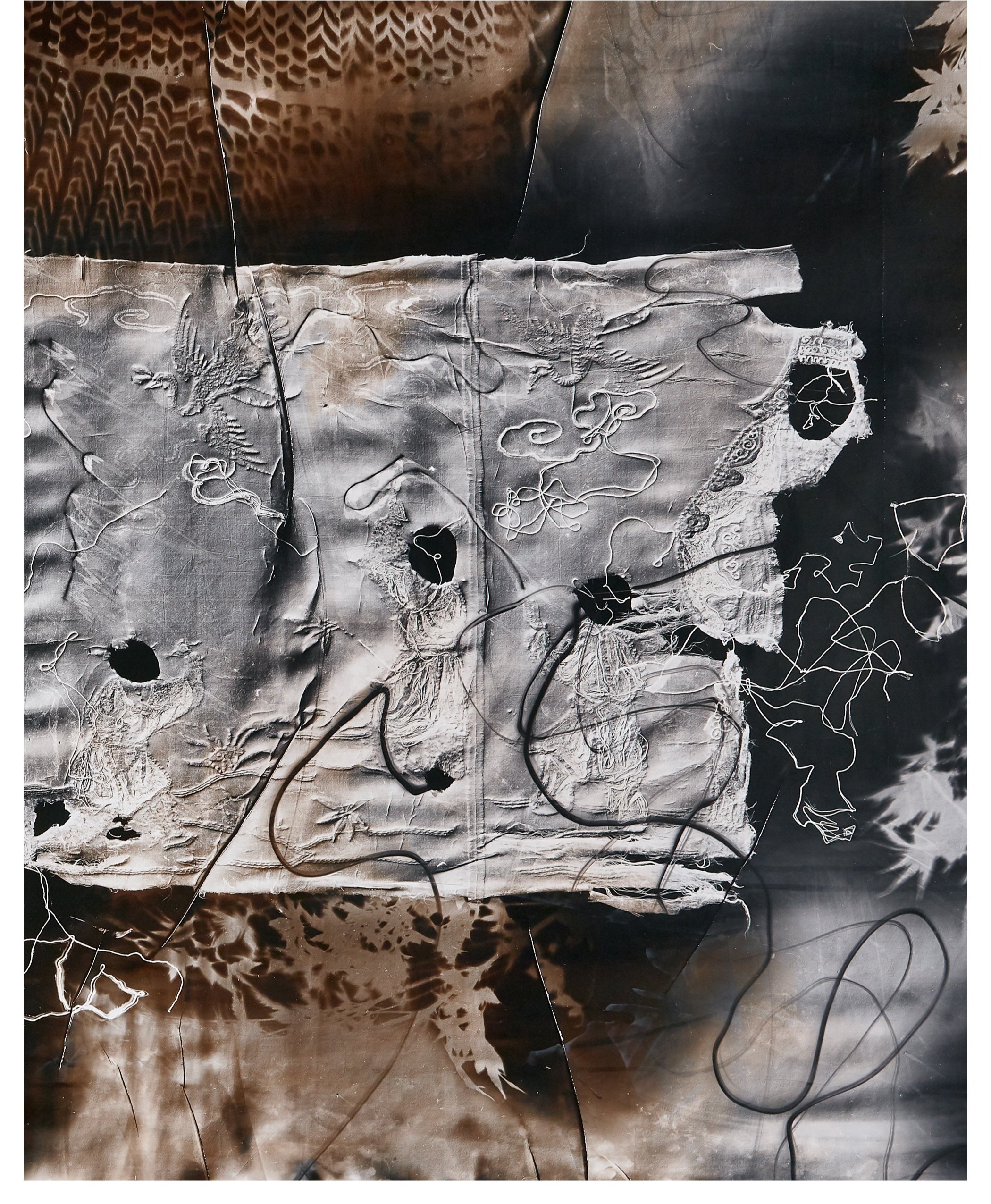

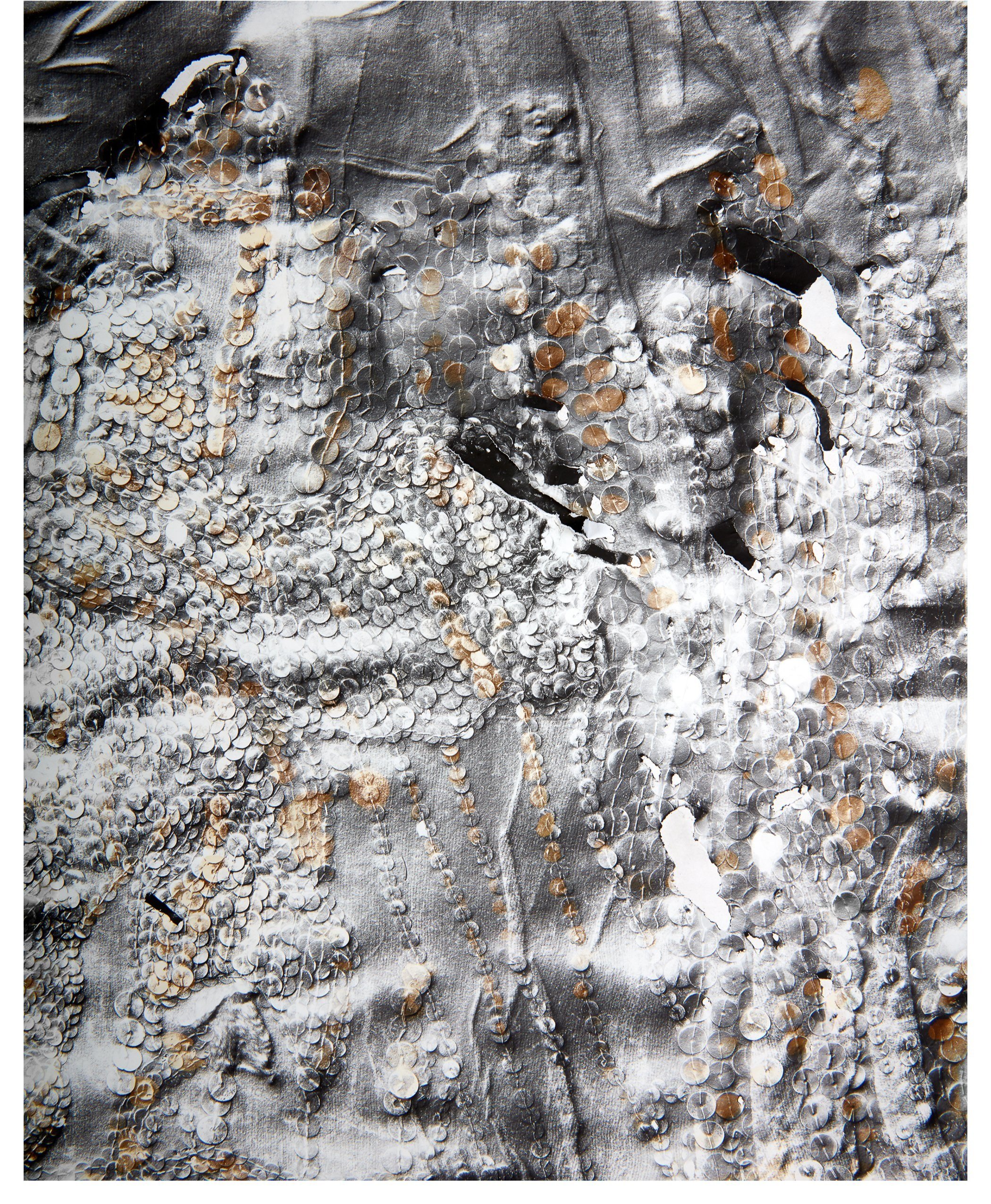

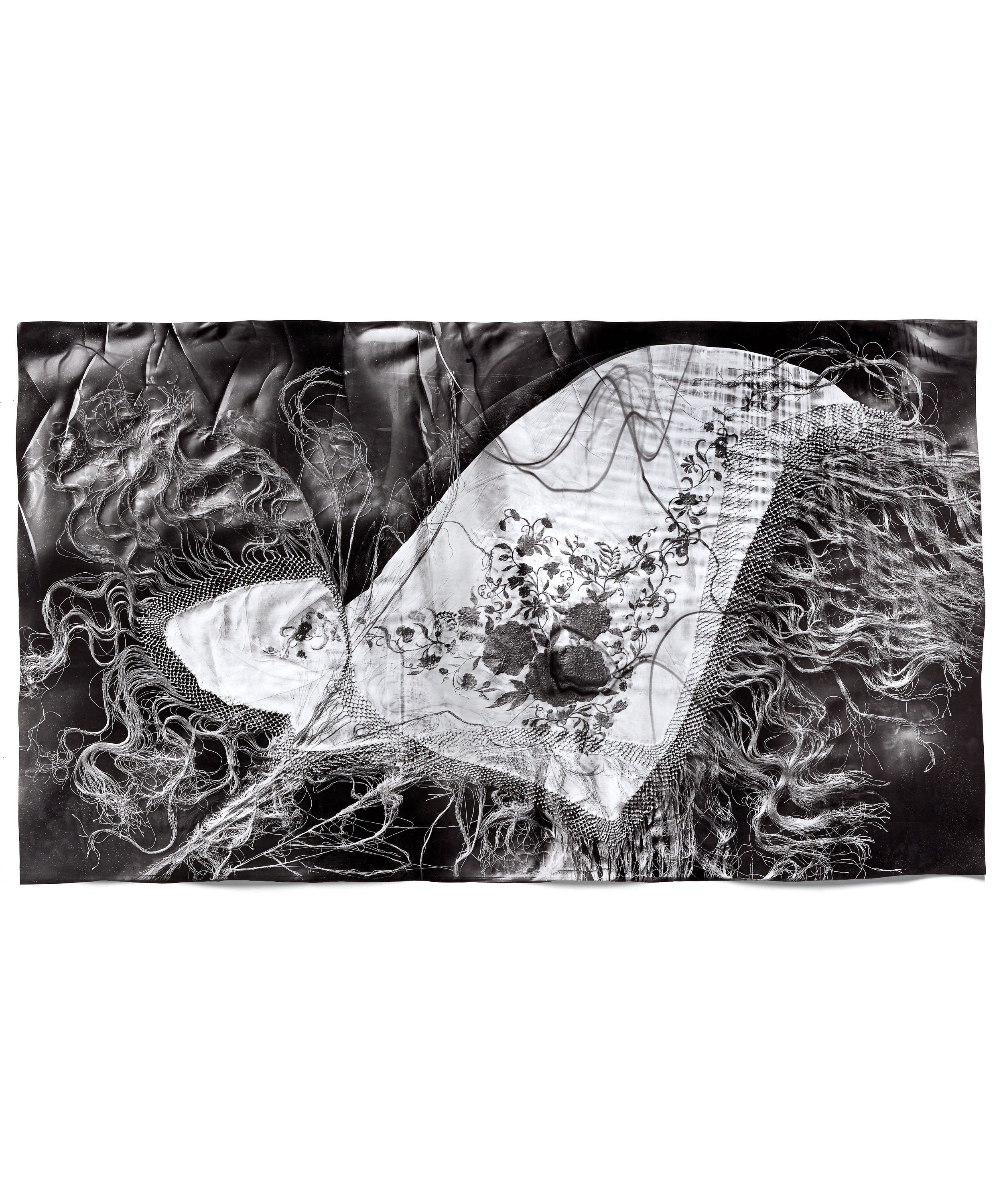

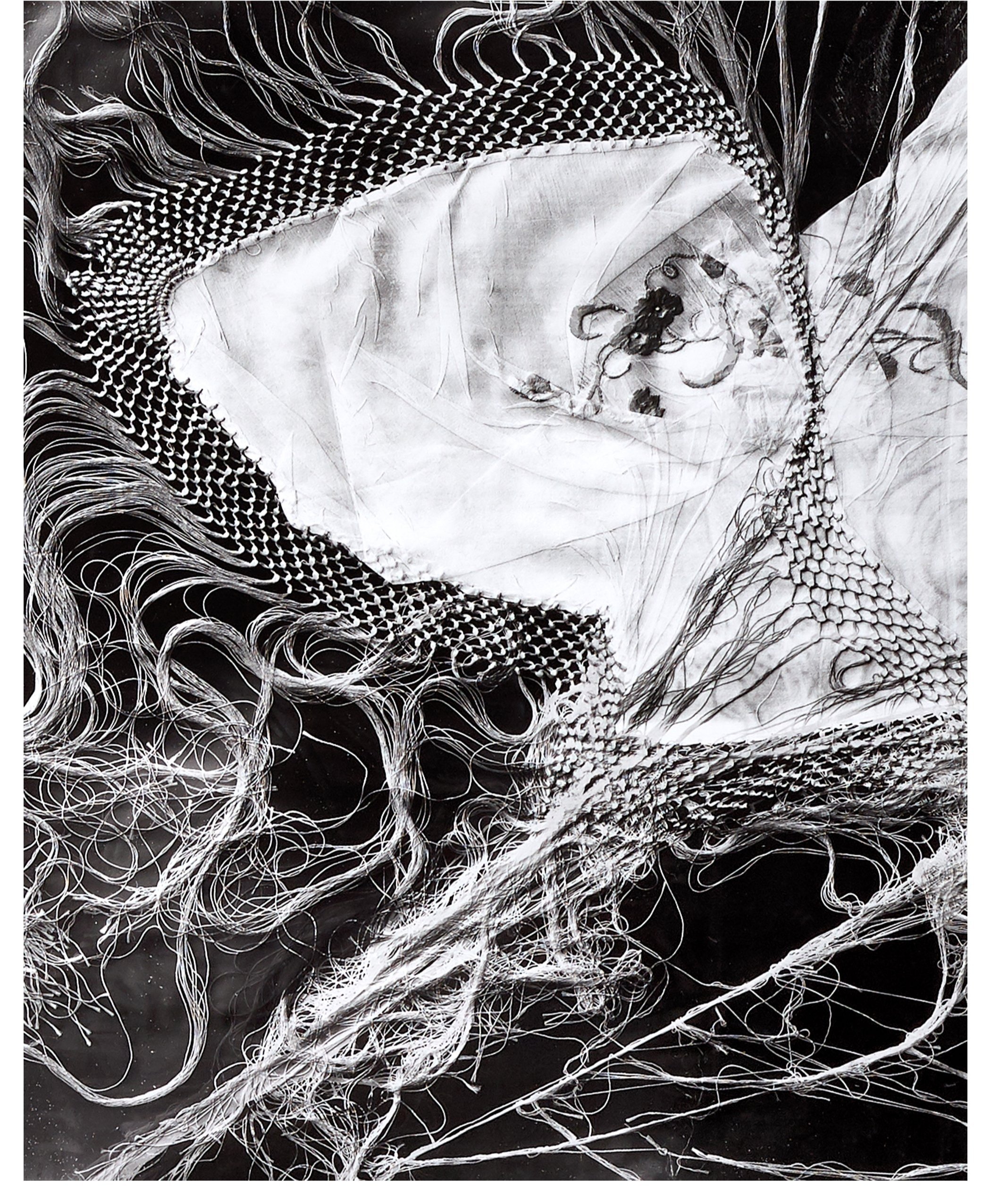

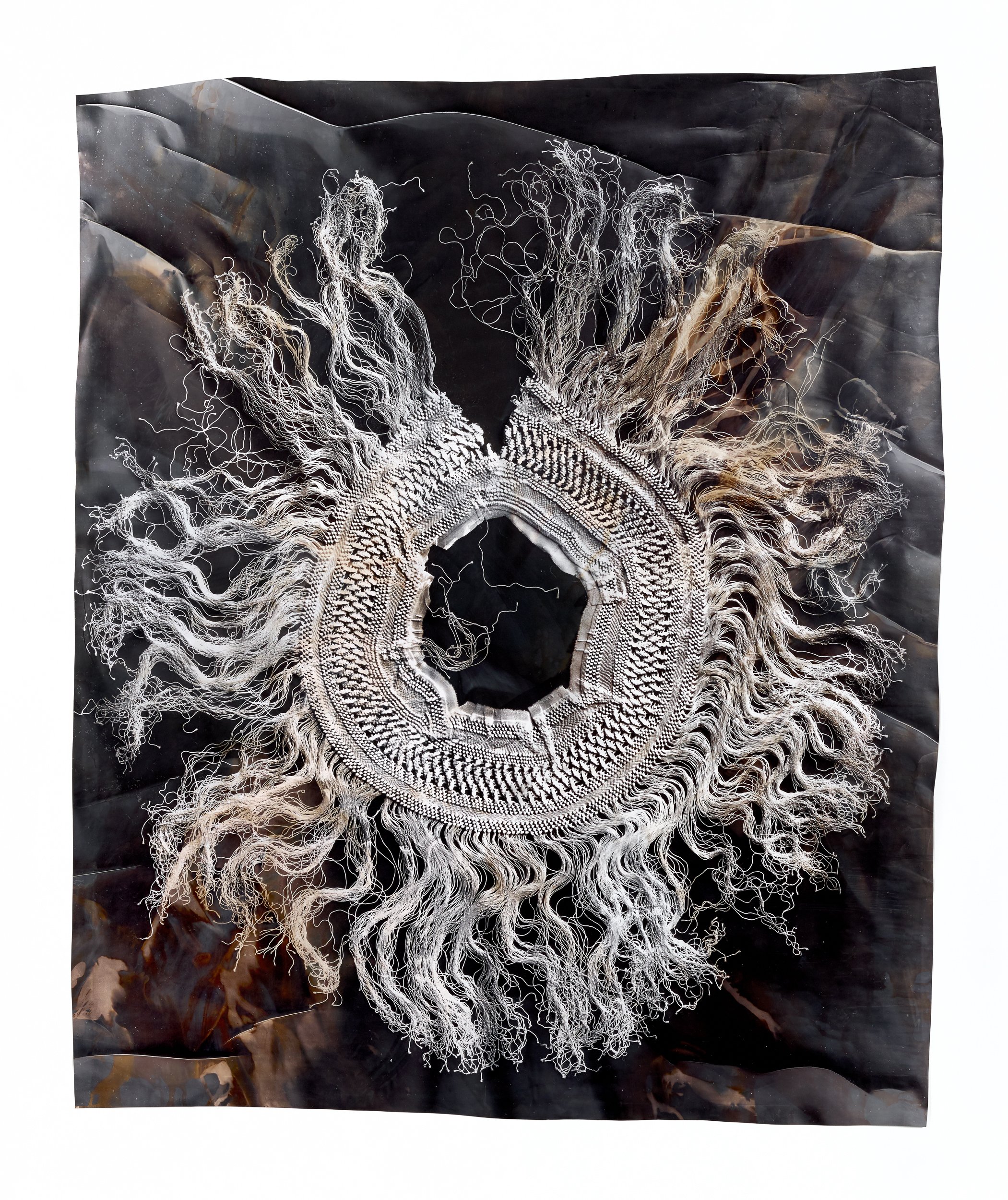

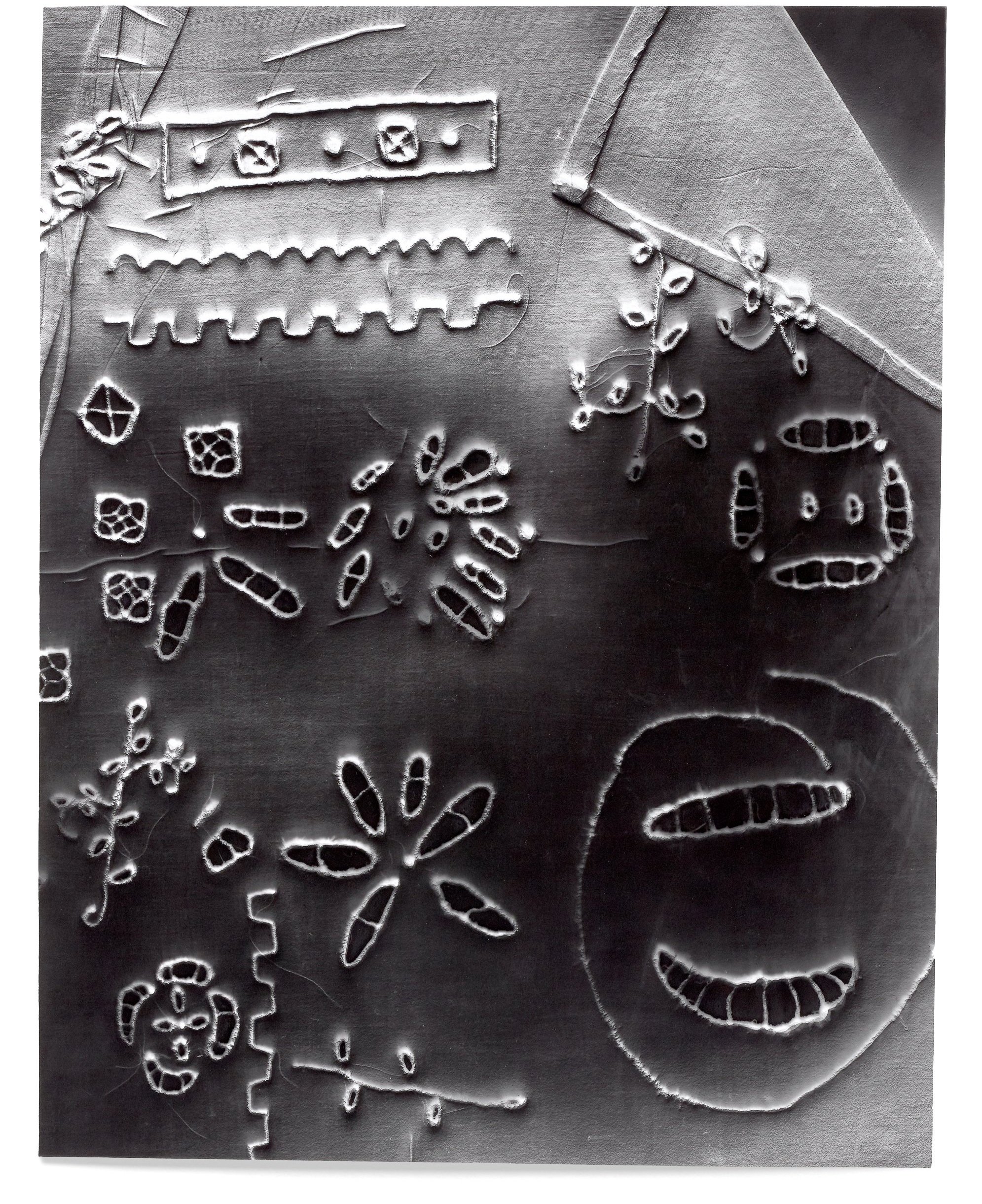

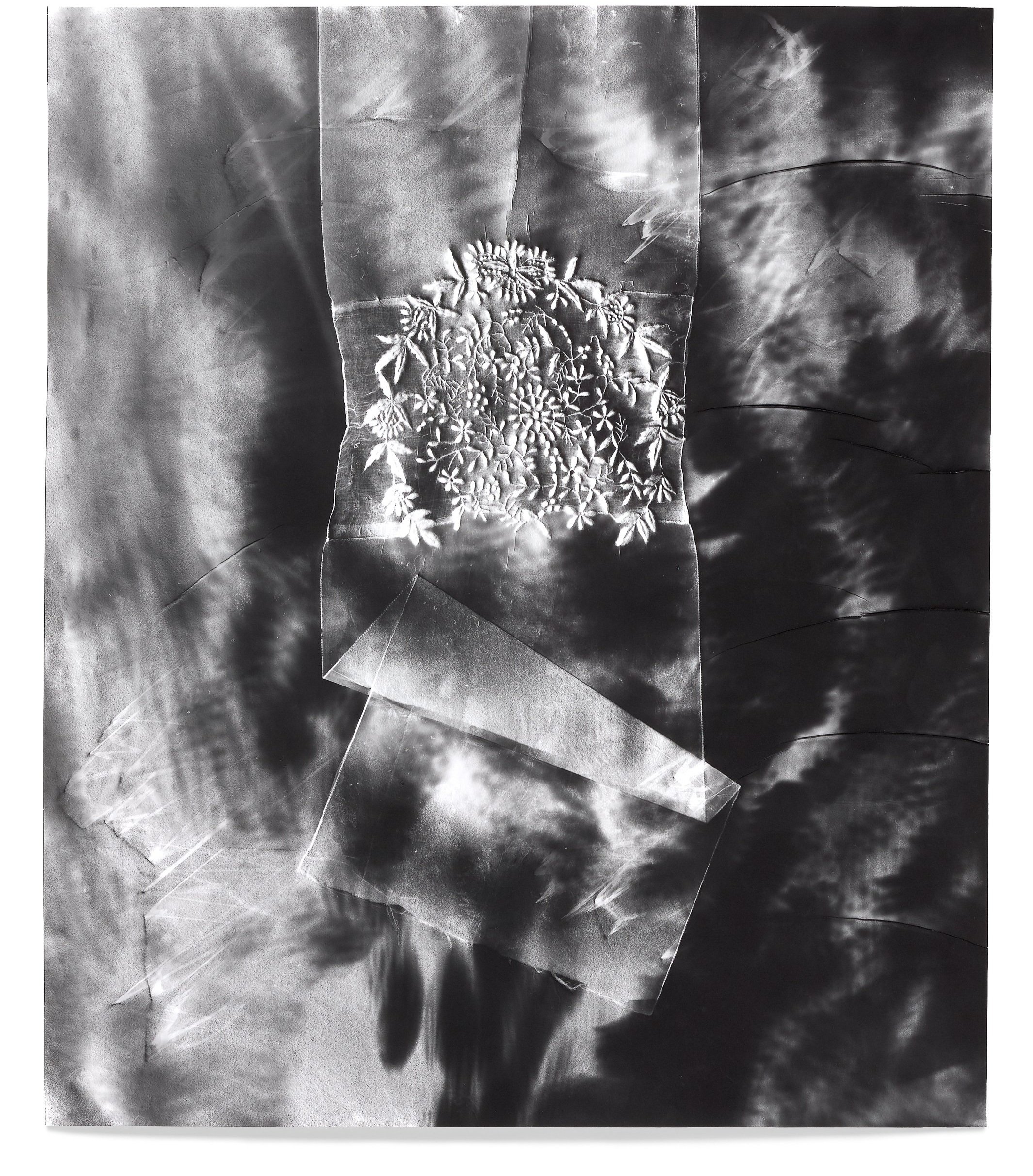

Photography, throughout its short history, has been modeled after the vision of an eye (a lens opens to record the light reflecting off of the world around it). But a photogram physically meets its subject and records the mark of an interaction. By further subverting photography’s intended use and making touch more primary than sight, I urge my already antiquated medium forward—asking it to transcribe texture, pressure and force as well as light—and to read the surface of the world in a new way. I use simple materials to make my “photographic rubbings” and “photographic reliefs,” relying on analog light-sensitive paper, my hands, a flashlight and sometimes an etching press. In darkness, I emboss paper with artifacts of material culture and patterns from the natural landscape, then I cast light onto the resulting textures. This method feels simultaneously like reading braille, praying and gambling. Acts of risk, faith and touching the unknowable are central to my practice. This unruly process reveals nuances beyond what my eyes or fingertips can confirm and invents new marks—vestiges of the friction and limitations of my materials. Yet, even when used in this crude and unbidden way, photography has a gift for describing reality in strange detail.

In Generation, I apply this method to textiles and women’s clothing from the last two centuries, objects that carry a rich legacy of touch—from the labor of their making to signs of wear. The history of textiles, clothing and style is comprised of a million stories of migration, cultural appropriation, and women’s labor and sexuality. Each article of clothing contains moments of individual innovation and decades of ordinary devotion. With every use, alteration or mending, someone has inscribed themselves onto these textiles. Just as each handmade garment was made through the patient labor of one woman’s body, so is it undone that way, worn down slowly over time, deconstructed or creatively cannibalized.

I begin by researching each garment’s origin, construction, intended use and broader representation, then I piece together a possible history from the available world of text and digital images. This is a poetic form of study, simultaneously an inquiry into what one can learn from a physical object—history having woven itself into the material—and an acknowledgement of how little I can know from this distance, as these textures show only the surface of someone’s experience and nothing of its interior. I seek to find a fracture, an insight that allows me to re-animate these objects and illuminate them anew from my own vantage point. My inquiry is evidenced in an artist book that is a companion piece to the photographic reliefs in this series. When amassed, this deluge of reference images becomes a visual history not only of the textiles themselves, but also of the changing notions of femininity and ornamentation, as well as the West’s relentless appropriation of traditional global fashions; it is a glimpse into a chaotic flowchart of influences, trends and the migration of objects that has shaped what women make and wear. My process of applying pressure—even to the point of a textile’s disintegration—is driven by my desire for haptic communication with women from a time and place different than my own.